Blog: Solving the 15 Puzzle

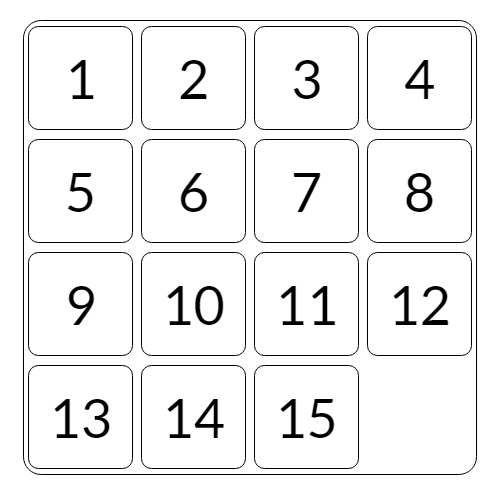

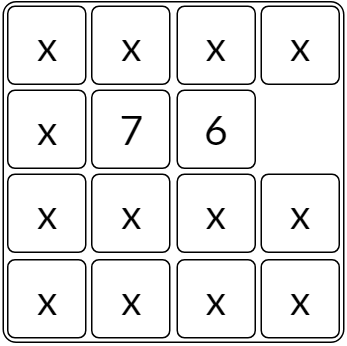

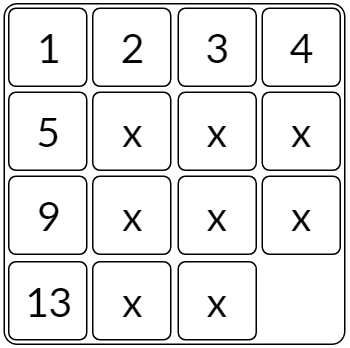

The 15 Puzzle is a classic sliding puzzle which consists of 15 square tiles numbered from 1 to 15 placed on a 4x4 grid, with one tile empty. The goal of the puzzle is to slide the tiles around to reach the solved state:

The puzzle also exists in various other sizes, such as the smaller 3x3 "8 Puzzle" and the larger 5x5 "25 Puzzle". In general, these sliding puzzles are collectively called the "n-puzzle" (also called the "(n^2-1)-puzzle"). This can be generalized even further to cover any rectangular pxq board sizes like a 3x4 "11 Puzzle".

Despite its simplicity, this century-old puzzle has modern applications for modelling and evaluating heuristic algorithms. In this post, I'll be explaining the different methods of solving a n-puzzle with the minimum number of moves.

Before we begin, you can play with an interactive n-Puzzle on my website which includes a solver using a static pattern database heuristic (keep reading to find what that is!) with various preset pattern partitions. The source code is available on my Github.

Optimal Solutions

Each state of the board can be represented as a node in a graph, and two nodes are connected with an edge if one of the board states can be turned into the other by sliding a tile.

Finding the optimal solution to a board is equivalent to finding the shortest path from the current board state to the solved board state. A common path finding algorithm is A*, which traverses through the search space using a heuristic which estimates the distance to the desired end state. While A* would work for solving the 15 Puzzle, its memory usage increases exponentially with the length of the solution. This is reasonable for the 8 Puzzle, as the hardest boards take 31 moves to solve.

For the 15 Puzzle, this upper limit increases to 80 moves.

Hence, solving the 15 Puzzle with A* can require massive amounts of memory. A better algorithm to use is a variant of A* called IDA*. Compared to A*, it is less efficient as it can explore the same nodes multiple times, but its memory usage is only linear to the solution length.

For a p x q puzzle, there are (pq)!/2 number of boards in the search space. So, the search space increases super-exponentially as the board size increases. This makes optimally solving large puzzles very impractical (the 35 Puzzle is the largest analyzed size that I could find).

To make it even worse, finding the shortest path that solves a board state is proven to be NP-Complete. As long as the heuristic never overestimates the distance to the goal (such a heuristic is called "admissible"), IDA* (and A*) will eventually find an optimal solution. While there's no perfect heuristic, the problem is to find increasingly better ones.

Heuristics

Misplaced Tiles

The simplest heuristic for the n Puzzle is to count the number of misplaced tiles. However, it performs horribly as the heuristic doesn't provide any information about how those tiles are misplaced, such as how far a misplaced tile is from being correct.

Manhattan Distance (MD)

Instead, we can sum the Manhattan distances of each tile from its current position to its solved position. This is effectively a lower bound on the minimum moves needed for each tile to reach its solved position. MD performs better than the previous heuristic, and is enough to solve all 8 Puzzle instances in a reasonable amount of time.

However, we're still far from a perfect heuristic. The main issue with Manhattan distance is that it doesn't take into account the interactions between tiles. It assumes each tile can move independently from the other tiles, resulting in a very low bound on the actual cost.

We can improve it by incorporating more of the board in the heuristic, and one way to do it is using linear conflicts.

MD + Linear Conflict

Consider two tiles that are in the same row or column, and their goals are also in the same row or column, but they're in the wrong order. According to the Manhattan distance heuristic, both misplaced tiles are 1 tile away from their end position. However, it's impossible to swap the two tiles in just 2 moves. In fact, at least 2 additional moves are needed to move one out of the way for the other one to move into its place.

The linear conflict heuristic adds 2 moves for every linear conflict in the board. This can be used in addition to the Manhattan distance by summing the two heuristics together.

Inversion Distance

The following two heuristics (Inversion Distance and Walking Distance) were both developed by Ken'ichiro Takahashi (takaken). You can read his description of them on his website (in Japanese). There's also a rough translation in English available here.

This heuristic builds upon linear conflicts and uses the idea of inversions.

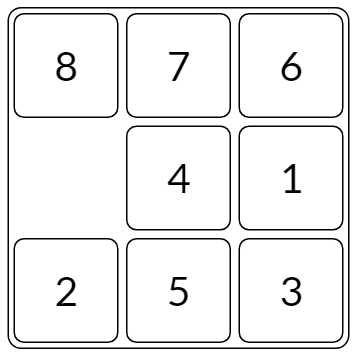

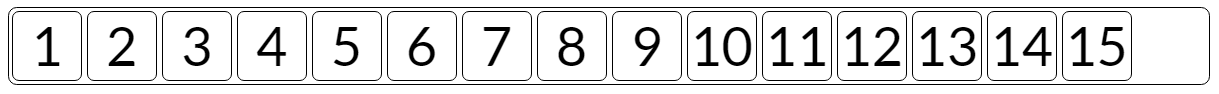

Consider unraveling the square into a single row of tiles (left-to-right, top-to-bottom):

We define an inversion to be when a tile appears before another tile with a smaller number. The blank has no number and cannot contribute to inversions. There are a few things to note about inversions:

- When moving a tile horizontally, the total number of inversions never changes. This is due to the blank not affecting inversions.

- When moving a tile vertically, the total number of inversions can change by only -3, -1, +1, and +3 [#1]. - First note that a vertical move will shift the tile 3 positions forward or backwards in our line of tiles. - There are two cases to consider, depending on the relative value of the three tiles we've skipped over: - Case 1: the three skipped tiles are all smaller (or larger) than the moved tile. - Moving the tile will either add or fix three inversions, one for each skipped tile. So, the total number of inversions changes by +3 or -3. - Case 2: two of the tiles are larger and other is smaller (or vice versa). - In this case, there's going to be a net change of +1 or -1 inversions.

One vertical move can fix at most three inversions. If we assume the minimum number of vertical moves needed to fix the inversions, that results in floor(invcount / 3). If there is a remainder, the remaining inversions can be solved with at least one vertical move per remaining inversion. This leads to a lower bound on the number of vertical moves required:

vertical = invcount / 3 + invcount % 3

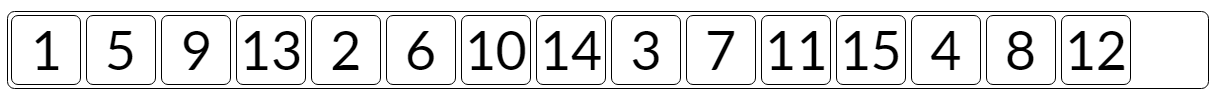

We can do the same for horizontal moves. However, the ordering is now top-to-bottom, left-to-right:

We need to compare the tiles correctly, as ordering by the tile numbers won't be enough. Instead, we need to compare the tiles by the location of their correct position. For the vertical inversions, that ordering happened to be the same as the ordering of the tile numbers.

Since the vertical moves and horizontal moves are mutually exclusive, we can sum the two lower bounds to finish our heuristic.

ID = vertical + horizontal

Note that the change in inversions from a single move can be determined using only the skipped row / column, instead of the entire board. This can be used to efficiently calculate a board's ID after a move is applied (a speedup by a factor of the size of the puzzle).

Walking Distance

MD and ID both worked by splitting the lower bound into vertical and horizontal components. We can incorporate aspects from both heuristics to create a better one.

The issue with MD is that it doesn't take into account the interactions between tiles. On the other hand, ID only considers these interactions, and doesn't care about a tile's distance to its end position.

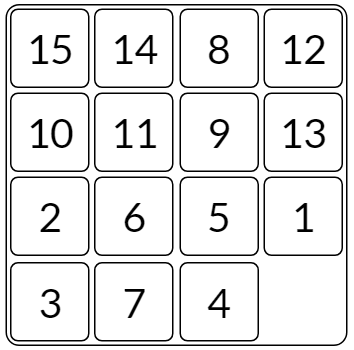

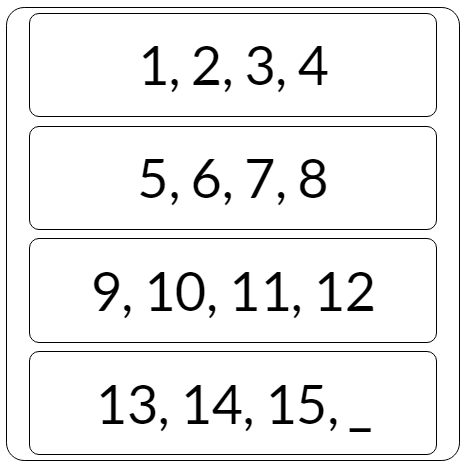

Consider grouping all of the tiles in the same row together, so that we have a 1xq column:

In our new column board, the only moves we can make consist of taking a number in a row adjacent to the row containing the blank, and swapping places with it. In the above case, we could move any tile in the 3rd row to the bottom, moving the blank tile up. The minimum number of moves needed to solve the column board is the vertical Walking Distance.

Just like MD and ID, we can calculate a horizontal Walking Distance for a "row" board, and take the sum of the horizontal and vertical components to calculate WD.

The advantage of WD is that it incorporates the MD of each tile while also considering conflicts with other tiles. One thing to note is that WD will never be less than MD, since WD is effectively MD + conflicts. This means that WD is strictly better than MD in every case!

Instead of calculating WD during the search, we can run BFS backwards from the solved state to get the WD of all possible row/column boards beforehand, and store their WD in a database. This vastly speeds up search time as finding WD takes as short as an array lookup. For the 15 Puzzle, there are 24,964 distinct boards to store, and the maximum WD value is 70. So, we could easily store each value in a byte, and our database would take up <25 KB of storage.

Pattern Databases

All of the previous heuristics are calculated during the IDA* (or A*) search as each board state is considered. This was fine since the heuristics themselves don't require a lot of time to calculate. However, we could take a different approach and perform calculations ahead of time. These cost of these calculations can be amortized across multiple solves of the puzzle, allowing for more complicated heuristics without sacrificing runtime.

We've shown above that WD can benefit from this tactic, but another type of heuristic that takes advantage of this method is a pattern database heuristic. In general, a pattern database contains the heuristic cost of all permutations of a section of the board, called a "pattern". These databases can be used as lookup tables when calculating the heuristic value of a whole board state.

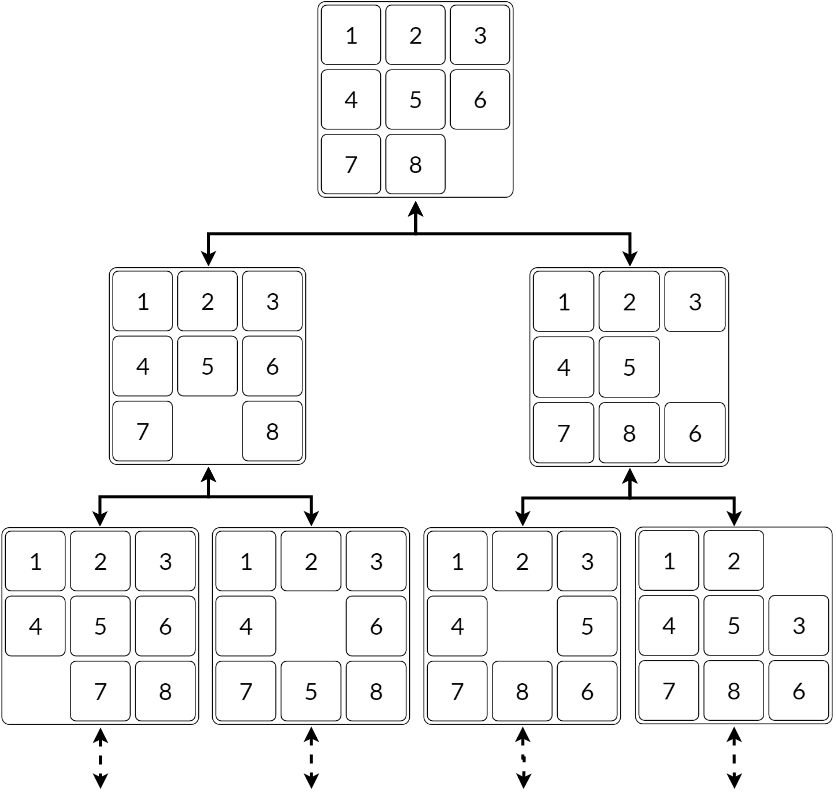

These databases can be computed by taking the end board state, and performing a single BFS backwards, reaching all desired unsolved states with minimal cost.

The following pattern database heuristics are taken from two papers written by A. Felner, S. Hanan, and R. E. Korf. Both are available online here and here.

Non-Additive Pattern Databases

Consider the set of tiles in the top row and left column, called the "fringe" tiles.

The number of moves required to solve just the fringe tiles depends on the position of the fringe tiles and the blank, but is independent of the other non-fringe tiles.

This pattern database will contain the number of moves needed to solve the fringe tiles of every permutation of the above board. Notice that we consider all non-fringe tiles equivalent

Also, solving the fringe tiles is a lower bound on the solution length of the entire puzzle, since only a subset of the board is checked. This is important to ensure the heuristic remains admissible.

Combining this with another pattern database, we can take the maximum of the two database values as an efficient heuristic.

Static Additive (Disjoint) Pattern Databases

One key aspect to note is if we used several pattern databases with mutually exclusive tiles (i.e. every tile is in at most one database), we could optimize by summing the database values rather than taking their maximum.

Another difference is to ignore the position of the blank in the board states. Each entry in the database contains the minimum number of moves needed to solve the pattern, for all possible blank positions. So, while we need to keep track of the blank when generating the database, it can be ignored in the actual entries.

When choosing patterns, we want to group tiles together that are near each other in the solved state since the pattern database contains interactions between tiles in the same pattern, and these tiles interact more than distant tiles.

Also, the heuristic will be faster with fewer, bigger patterns, but will take exponentially longer to generate and contain more entries. For the 15 Puzzle, a seven-tile database contains 57,657,600 entries, and an eight-tile database contains 518,918,400 entries. In general, a m-tile database for the n-Puzzle will contain P(n+1, m) = (n+1)! / (n+1-m)! entries.

Note that MD is a trivial example of a disjoint database where each tile is its own pattern. Since each pattern contains only one tile, it doesn't consider interactions between tiles.

To optimize on storage, we can construct patterns of the same shape (including rotations and reflections) and use a single database for them. This includes a slight overhead to perform the correct lookup, but can save an entire database-worth of storage.

Dynamic Additive Pattern Databases

Instead of using the same pattern for all board states in the search, we could optimize by picking an efficient pattern depending on the board state. This pattern would be chosen to maximize interactions between the tiles of the board state, and could do better than sticking with one pattern throughout the search. This is the main concept behind a dynamically partitioned database heuristic.

In order to generate these patterns during the search, we first generate a database beforehand. For all pairs of tiles, we calculate the smallest number of moves needed to turn all starting positions of each pair to their solved positions. We'll call this the pairwise distance. In most cases, this is simply the sum of the MD of both tiles. However, if the pair are in a linear conflict, the pairwise distance will be more than the sum of the MDs.

Similar to the previous heuristics, these pairwise distances can be calculated by performing a breadth-first search backwards from the solved board state. Each state in the database is composed of the positions of the two tiles and the blank.

To use this heuristic during the search, we need to pick a set of pairs such that each tile appears in exactly one pair. This is crucial in order to avoid overestimating by counting a tile more than once. Once we have the non-overlapping pairs, we can sum their pairwise distances to calculate the heuristic. If there's an odd number of tiles (such as in the 15 Puzzle), the leftover tile contributes just its MD to the sum.

This is where the dynamic part comes into play. Rather than picking any acceptable set of pairs, we can pick the set that maximizes the pairwise distance sum, as that will be more efficient for the search. Since this maximal set depends on the board state, the pattern must be calculated during the search (dynamically).

In order to find this set, we can visualize each tile as a vertex in a graph with an edge to every other tile. Each edge has a weight which is the pairwise distance of the two tiles it connects. To find the maximal set is to find a set of edges without common vertices, such that the sum of their weights is maximized. In graph theory, this problem is called the maximum weight matching problem, and can be solved in O(n^3) time.

In practice, this heuristic evaluates fewer board states than the static variant, and uses less storage for the database, but takes longer to solve. This is due to a few factors:

- Dynamic patterns are better at capturing interactions than static patterns, since those patterns are optimal.

- There are fewer pairwise distances (

O(n^4), wherenis the number of tiles) than unique pattern states (O(n!)). - Dynamic patterns take more time to calculate due to the matching (

O(n^3)) as opposed to several lookups (O(n)).

The dynamic pattern heuristic can be further optimized, but that's beyond the scope of this post. You can read more about them in this paper.

Conclusion

Here is where the list of heuristics end for now. After all this, you may ask yourself which heuristic is the best for you?

There is a general trend of trading faster search time for bigger lookup tables. It is simply more efficient to perform calculations beforehand to avoid slowing down the actual search.

Currently, the fastest single heuristic to optimally solve the n-Puzzle is to use a static additive pattern database, using the largest patterns you can generate and store. For the 15 Puzzle, a 7-8 partition is enough to solve nearly all board states on the order of tens of milliseconds, and requires ~550 MB of storage.

With sufficient storage space, you could even use multiple database heuristics and take their maximum, such as Walking Distance and 5-5-5 pattern database.

If you have tighter storage limitations, even a 5-5-5 partition can solve boards in under a second using only 3 MB of storage, which is very reasonable to implement. Leaving the category of pattern databases, Walking Distance is fairly efficient on its own, with 25 KB of storage needed.

If you plan on avoiding databases altogether, your best option is probably to use the maximum of MD and ID. At this point, you will be sacrificing a lot of speed for no external storage or precomputation. This is easily sufficient for the 8 Puzzle, but might not be enough for harder instances of the 15 Puzzle.

Extras

Parity Proof

Some of you may recognize that these are all odd number changes. Keep in mind that a change can only happen with a vertical move, so the row number of the blank changes by +1 or -1. If we add the row number of the blank to the number of inversions, then this sum can only change by -4, -2, +2, and +4. This means the parity of this sum (number of inversions + row number of blank) stays constant with every valid move. Using this fact, it is possible to show that two board with different parity cannot be converted into each other. This also means that the solved board with the blank in the bottom-right corner, and the one with the blank in the top-left corner cannot be turned into one another.